For those proxies to be useful to us they should meet just three criteria: 1) they must be causal to the long term outcome we desire, 2) they must themselves be measurable with the toolkit, timeframe and other constraints that exist for us today, and 3) they must be amenable to our interventions.įor the broad goal of promoting children’s optimal healthy development, there are a number of proxy measures that meet these criteria. If we know that A causes B and we believe that B causes C, then shouldn’t we believe that A causes C? If this transitive argument is reasonable, then perhaps we should seek out the intermediate points that hold the most promise. This is where proxy measures can have great effect. We must ask, “If the theory is true, what are the implications?” Instead, like Einstein and countless other great thinkers and scientists, we must push the theory forward. What does a practitioner do in the meantime? We can hardly sit around for a century waiting for the measurement to catch up to the theory. The gravitational wave announcement gives us hope that that day will eventually come. We may need yet more creativity and measurement prowess.

#Gravitational waves discovery for kids full#

While we have only scratched the surface of the power garnered from these new tools and even if we realize their full potential, we may still be left short of seeing the long-term impact of a specific experience on an individual. These along with many other efforts promise to relentlessly advance our ability to tease out ever more subtle impacts of our interventions. examining various effects of genetics or behaviors on individuals). to measure the effect of social interactions in a self-organizing, complex system like a city neighborhood) to “Big Data” in data analytics (e.g. Whole bodies of study have been lifted and borrowed from fields ranging from “Complexity Theory” in mathematics (e.g. Researchers and practitioners have had great success in enhancing our techniques. So, what do we do? One approach is to build ever more refined measurement tools to isolate these many influencers. This dual reality of knowing that there is influence yet not being able to sufficiently measure it has the potential to leave us paralyzed in inaction. We use words like “complexity” and “multi-modal” to explain our failure to isolate these impacts. There is no method for us to say definitively that a specific experience is responsible for a specific result in a specific child because all experiences are interrelated and all children are unique in both their genetic make-up and their life experiences. Like the infinitesimal phenomenon of gravitational waves in Einstein’s day, other factors can drown or mitigate the impact. Yet the influence that any single experience has on a child is so minute that we are unable to measure its incremental affect. They also implicate that both positive and negative experiences influence children’s health, their social and emotional growth, their educational success, their economic opportunities, and other areas. These are fundamental principles, like Einstein’s equations, that build the foundation of our work. We now know that both nature and nurture play significant roles in a person’s life-course and health outcomes. In the study of childhood development, the 1990’s established solid evidence that experiences early in life produce long-term implications to health, well-being and economic success. And yet it is also reassuring to reflect that as time passes, our work will someday be substantiated and validated through yet-to-be discovered measurement techniques. It is humbling to think that the success of our work may only be observable decades after it is put into service, perhaps long after we leave this earth.

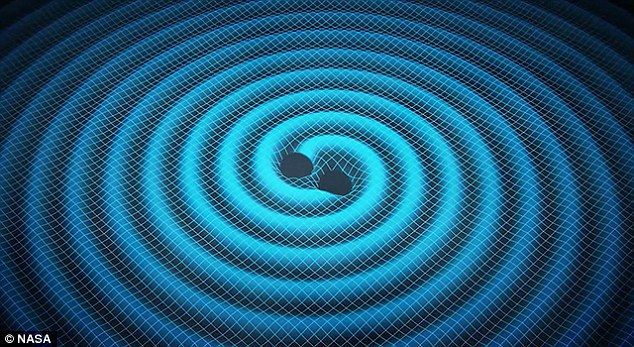

The thought that a discovery can be made a century before the invention of technology sufficient to measure its effect can be both humbling and reassuring to those of us seeking evidence-based solutions to modern challenges affecting child health outcomes. How does this relate to child health? Read on! In addition to validating the theory, scientists now have a new tool – a gravitational telescope – that they can use to map and explore the universe in a revolutionary way. The implications for this discovery are huge. One hundred years after Albert Einstein first predicted their existence in his groundbreaking theory of general relativity, scientists detected gravitational waves for the first time. Big news hit the scientific community in February about gravity.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)